Way back in the late 1990’s the U.S. experienced what is now referred to as the Tech bubble where internet startups became wildly overvalued in a wave of optimism that ended badly for many investors. Over the last few years a financial crisis has enveloped the globe that many refer to as the bursting of the Debt bubble, a process of dramatic deleveraging from a prior euphoria of financial innovation, shadow banking and subprime securitization that separated risk from debt origination.

These are not the first financial bubbles the world has experienced, nor the last. They are just those still weighing on recent memory. But people tend to move on. Recently published gross domestic product numbers show a much improved level of growth here in the U.S. and in many economies around the world. So should we conclude that our latest problems have passed and we can move on to better times?

The Cure is worse than the disease

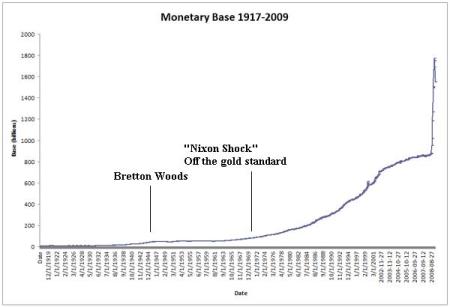

We will be debating for years whether or not the enormous government stimulus programs were the appropriate response to the financial crisis which began in 2008. Combined with massive liquidity measures by the world’s central bankers, these government-sponsored solutions were substantial by any historical standards and will have consequences for many years to come. But how will all this play out? As our global economy has experienced the pain of deleveraging, have we merely shifted debt from the private sector to the public? Government budget deficits world-wide are on the rise. Some of these appear to be at unsustainable levels.

Here in the U.S. there is much concern about our fiscal future. Rising government debt levels and deficits projected far into the future do not instill confidence – even if the U.S. is the largest and most productive economy on the planet.

In a perfect economic world, a government that runs persistent deficits and pursues monetary expansion can expect to be disciplined by the markets through a process of currency devaluation. It is somewhat of an anomaly that the U.S. dollar has not fallen dramatically in light of recent history.

In fact, long before our recent financial problems, the U.S. dollar was under downward pressure – responding to many years of government expansionary policy. But the U.S. was able to carry on running both budget and trade deficits in part because of the unique status of the U.S. dollar as the world’s reserve currency. The demand for dollars from an expanding global economy was immense. As the world economies became more and more connected, an increasing demand for U.S. currency to facilitate trade and investment sheltered the U.S. from the normal constraints of fiscal impropriety. But still the U.S. dollar was under downward pressure. Central bankers posited accumulating reserves in alternative currencies, or baskets thereof.

Recently, the status of the U.S. dollar in international markets has become increasingly difficult to understand. The financial crisis itself caused a flight to quality that, at least temporarily, boosted the U.S. dollar. Then when retrenchment began again, the Euro stumbled as a comparative currency when government deficits in Greece and elsewhere within the Euro community began to chip away at the confidence factor required to sustain its value. It is not clear today whether the U.S. dollar is appreciating, depreciating or maintaining its position. So what is the proper value of the dollar?

Floating Boats

In centuries past, currencies were backed by gold or silver and could not survive without a right of convertibility to sustain its value. The great global expansion of the 2nd half of the twentieth century was fueled in large measure by the adoption of the U.S. dollar as the world’s “reserve” (trading) currency. It was formally backed by gold to insure stability. This allowed other nations to tie their currencies to the steadiness of the dollar; whether on a fixed, ranged or free float basis. Any government fiscal impropriety would be punished by automatic currency devaluation against the dollar resulting in lower living standards for its people. There was such a thing as market discipline. But in 1971, the mighty U.S. dollar, to which all these currencies were tethered, was freed from its moorings when Nixon announced the U.S. was abandoning the gold standard. The dollar too would now float. So today we are in a world of pure floating currencies. Like unanchored boats bobbing in an uncertain sea, each nation measures its currency relative to others, including the U.S. dollar. So what is currency worth these days? There is no convertibility of any currency to a measure of stable value. With all boats floating, can we tell if the seas have risen or fallen? Does it matter?

Without any reasonable alternative to the U.S. dollar as a reserve currency, we’ve managed to simply continue along for the last 39 years. However it has become increasingly apparent that an adjustment might be necessary in the future. The European creation of the Euro, the Chinese government statements about moving toward an SDR (special drawing rights of the IMF) solution and the suggestion of some oil exporting countries that a currency basket should replace the U.S. dollar for trading; all of these have been a reaction to the uncomfortable place we find ourselves in with our reliance on paper currencies without a true measure of value.

The Perfect Storm

So here we are at a time in history where our latest crisis has forced governments to take on extraordinary debts, run extraordinary budget deficits and engage in substantial “quantitative easing”. Indeed we are also seeing governments fight for their domestic economies through subtle protectionist policies that include a temptation, perhaps an incentive, to devalue home currencies.

Monetary expansion, simply printing money, has the advantage of dealing with most of the issues facing governments. It has one other advantage, especially in the case of the large debtor nations such as the U.S. Inflation, which one would expect after significant monetary expansion, favors the debtor. What better way to deal with excessive debt than to simply devalue it? Without the nuisance of a gold (or other) standard of convertibility, printing money may be the politically expedient solution. Everyone intuitively knows long term government deficits and monetary expansion make for bad policy, but how bad? And when does one have to pay the piper? And are not steps these justified, at least for now, given our economic conditions?

If the U.S. expands its money supply, won’t every other country be compelled to do likewise just to stay even and avoid the risk of upward currency revaluation with its inherent trading penalties?

Without stable currencies on the one hand or discipline and leadership from the U.S. on the other, we are in uncharted waters. The long-term temptation for governments to expand their money supply could be overwhelming. Volatility and expansion of currency markets could be the norm with long term implications of global inflation. The responsibilities thrust upon the world’s central bankers have never been greater.